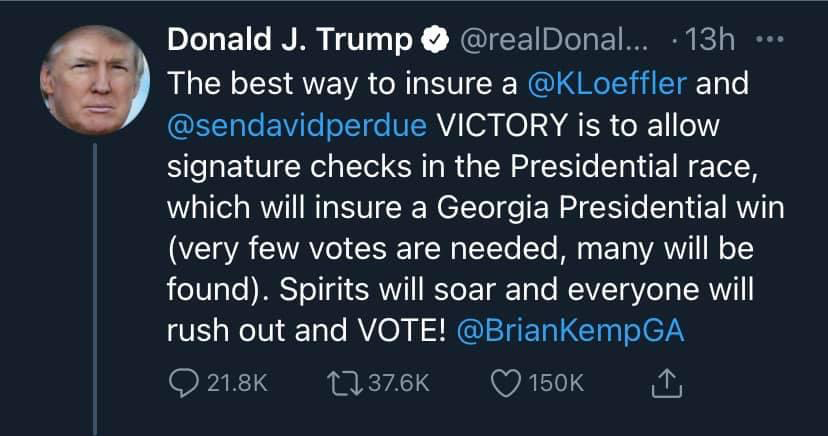

The president tweeted late last week that, “…the best way to insure a [Sen. K Loeffler] and [Sen. David Purdue] VICTORY is to allow …”; the question we are here to settle is not the veracity of his tweet, but rather that of his grammar — specifically using insure rather than ensure.

As an aside, we acknowledge no shortage of near-similar sounding words (nay, homonyms) that are grammarian trapping pits: Effect or affect; vane or vein; heir or air. Even this corny joke: What did the hunter say while offering comfort to the distressed deer? “Oh, dear, there, their, they’re.” (I know, bad.)

Throw in assure, which means a person offering confidence that something will or will not happen, and you have a real milieu for the confusion. Or, not really, because while some authorities consider insure and ensure interchangeable, it’s a fairly settled debate – at least in America. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, both assure and ensure came into English in the late 1300s, assure from Old French asseurer, “to reassure, calm, protect, to render sure,” and ensure from Anglo-French enseurer, “to make sure.” The word insure appeared around 1440 as a variant of ensure. It took on the sense of “to make safe against loss by payment of premiums,” in 1635. Before that, assure enjoyed that meaning, too. Today, insure has won as the word having to do with compensation for financial loss (e.g. “The violinist insured his hands with Lloyd’s of London.”). This use of insure applies on both sides of the Atlantic. The confusion that arises with insure vs ensure stems mainly from another definition: “to make certain that (something) will occur.” For example: “We wish to ensure the safety of our passengers. Some speakers of American English would use the spelling “insure” in this context, but most go with “ensure.”

According to the AP Stylebook, these are the guidelines journalists follow:

- Use ensure to mean guarantee: Steps were taken to ensure accuracy.

- Use insure for references to insurance: The policy insures his life.

Continental European “life assurance” companies take the position that “all policy-holders are mortal and someone will definitely collect” thus assuring heirs of some income. American companies tend to go with “insurance” for coverage of life as well as of fire, theft, etc. The bottom line: A grammarian could make an argument that the president’s tweet could be, technically, accurate (at least grammatically), but throw in elements such as syntax and usage standards, and it just opens [the president] up to more scrutiny; the tweet’s content notwithstanding.